The Inverted Periodization Training Method

Training, October 02, 2015

The inverted periodization model for triathletes is based on starting training cycles building a foundation that involves, technique, strength and speed rather than laying an aerobic endurance base, as with traditional periodization models. In training and coaching for almost 20 years now, I noticed with myself as well as other athletes of all levels of ability, that the long slow training done at the beginning of the season, not always is the best training approach. For most coaches and athletes out there, focus still on increasing what we called “Aerobic Engine” and I ask : “How much can we gain by adding extra slow miles to our training? 2 or 3% in performance? Now how much can we gain by developing proper motor skills and technique, strength and speed? I bet way more than 10%

The Inverted Periodization Training Method by Sergio Borges

Since I started to coach athletes over 20 years ago, I always contested the traditional method of training that was available at the time. The traditional periodization that implies that ideally an athlete can only peak for an event one or maybe two times per year made no sense based on what I had experienced and started teaching others. As an athlete myself, I wanted to do well in most races of the season and not only in one or two.

In addition, I noticed the strong lack of development of proper motor skills, technique, speed and strength during the "base phase" that so many training partners religiously applied to their training. In fact, most of them started the "base phase" faster than when they finished, and faster than their season races! Obviously it made no sense adding volume in training when the basic foundation of skills were not yet developed!

Today I see many athletes with poor motor pattern development increasing their chances of injury and poorer performance due to the unsuitable volume they do during the base phase of the traditional "periodization" training approach. I guess for many, the fear of "not conquering the distance" is responsible for most of the over-distance training done out there -- and many of the mistakes!

Not satisfied with the information I was getting from coaches and books to explain the reasoning behind using a traditional periodization theory for multisport training, I began to develop an alternative way of training that culminated in an article about "Inverted Training Periodization" that was published in the USA Triathlon Coaching Journal in 2003. As the name implies, inverted periodization focuses on developing technique, strength and speed first and endurance closer to your event(s).

More and more there are increasing numbers of coaches and sports scientists contesting the traditional periodization of training. The basis of training periodization was founded several decades ago when scientific knowledge was far from complete and athletes' workloads, results, and demands were much lower then they are currently. At that time traditional training periodization as a division of the whole seasonal program into smaller periods and training units was proposed -- and generally accepted without much challenge.

Due to the small number of publications and the reasonably small population of scientists studying the field, this "traditional periodization" was republished many times and became a universal and monopolistic approach to training planning and analysis without much debate or study. However, recently further progress in sport science has reinforced the extreme contradictions between traditional periodization and the successful experiences of prominent coaches and athletes.

In triathlon especially, it has become clearer that athletes guided solely by heart rate monitors and powermeters or those who follow a pre-determined training cycle using the principles of traditional periodization (one in which there is a "base phase" complemented by the unchallenged, generic approach of training for 2 or 3 weeks followed by a recovery week) rarely reach their full potential and are often prone to injury, poor focus and a lack of self-awareness. Most of the athletes today are guided only by "numbers" and often lose their ability to interpret their bodies' responses to training.

Further, it is becoming increasingly clear that triathlon is littered with the wreckage of professional and age group athletes who have destroyed their body's immune function, endocrine balance and biomechanical health often permanently or for very long durations due to highly catabolic approaches to training -- too much volume, too long "intense" sessions, little explosive speed or strength built into their training, and a general lack of emphasis on basic motor skill development. As a result, the strong focus on aerobic "gains" without the corresponding balance of more anabolic training sessions leads to increasing breakdown, generally evident in increasingly poor performances, greater fatigue, lower sex drive, more injuries, inability to concentrate, "puffiness" and weight gain, blood sugar fluctuations and insulin resistance and a littany of other symptoms.

The negative consequences of traditional periodized training have begun to be outlined in sports science literature as a pattern of drawbacks and outright contradictions between traditional theory and desired outcomes, including:

1) Inability to provide multi peak performances during the season (one shot Charlie)

2) Drawbacks of long lasting mixed training programs (an emphasis on "zone training" and aerobic capacity makes you slower)

3) Negative interactions between non-compatible workloads that induced conflicting training responses

4) Insufficient training stimuli to help highly qualified athletes to progress, as a result of mixed training (too tired to train properly)

However, unlike traditional periodization, which usually tries to develop many abilities simultaneously, the Inverted Periodization applies training stimulation of carefully selected fitness components for a set block of time, an approach sometimes referred to as "Block Periodization."

In his recent book about Block Periodization , Dr. Vladimir Issurin comments: "The basis of contemporary training was founded several decades ago when scientific knowledge was far from complete and athletes' workloads, results, and demands were much lower then they are currently."

As our sport evolves, we triathlon coaches and athletes need to acknowledge the increasing evidence of flaws in the general approach to training that is common with the approach used by many major coaching companies today. The Inverted Periodization provides an alternative to training that might better suit athletes' needs. "Thinking outside of the box" should be the general rule for any athlete or coach looking to improve his or her abilities. If you feel that you have reached a plateau in your training, if you're constantly tired and have yet to reach your goals, then maybe it's time for a change in your training method!

The inverted periodization

The inverted periodization model for triathletes is based on starting training cycles building a foundation that involves, technique, strength and speed rather than laying an aerobic endurance base, as with traditional periodization models. In training and coaching for almost 20 years now, I noticed with myself as well as other athletes of all levels of ability, that the long slow training done at the beginning of the season, not always is the best training approach. For most coaches and athletes out there, focus still on increasing what we called “Aerobic Engine” and I ask : “How much can we gain by adding extra slow miles to our training? 2 or 3% in performance? Now how much can we gain by developing proper motor skills and technique, strength and speed? I bet way more than 10%.

For most athletes, the long endurance base training is done in the winter and spring months, so by March or April, athletes are at the highest level of endurance possible. But unfortunately for most athletes, they end up racing in June and July and by this time; the level of endurance is lower than when they started in April.

If we look at a triathlon event itself, where endurance is 85% of the race, we want to arrive at the race at the highest endurance level possible. The same is true for the racing season—we want our highest levels of endurance at race time.

I believe that by doing your endurance training close to the race instead, the athlete will race with a higher aerobic capacity. As we know, contrary to speed, motor skills and strength, endurance is the easiest to gain but also the easiest to lose. And for athletes living in North America and Europe, trying to log long miles on the bike and run can be challenging during winter and most of spring season.

Root of Inverted Periodization Training

The idea is not new, and it has been used in Europe for some time in sports like running, swimming, cross country skiing, etc. I believe the cold weather, forced Europeans to try a different approach of training that with less volume and instead, work on different aspects of the training like: technique, speed and strength during the winter and part of the spring months. After researching for a different approach in different sports, I adapted this concept to triathlon. What I saw happening here with athletes is that they start training in the first part of the season by developing a huge aerobic base, then start cutting the volume down and start adding speed work as the season gets closer. When back to speed work, athlete feels really slow (lost of efficiency, mobility, elasticity, speed and strength due to slow long training) and desperate, do improper intensity (length and repetition) increasing the chance of getting injured. Not only that, athletes start to question themselves about their endurance (the feel of not doing enough) and they start adding volume back again, but they want to keep the high intensity speed work, which leads them to over train and possible injuries. This frequent occurrence is why I decided to change the training method I was using.

How Early Endurance Training Works Against Speed

When they train for long-distance races, most athletes end up over doing in volume. I guess the fear of not finishing a race could be the why. Many of our athletes have a sufficient enough endurance that they could do an Ironman race back-to-back. But, what they really want is to go from start to finish as fast they can, right? It doesn’t matter if they can do it back-to-back. As an athlete, specially if you have been training for a while, it is so much easier to gain endurance than speed. So, when athletes spend 3 or 4 months doing only endurance, they end up staying away from speed workouts far too long. When they get back to speed work, they lost most of their last season speed, mobility, elasticity and strength. I like to say: “The fast-twitch muscle fiber has been sleeping so long, it makes the process of getting fast again longer and more difficult”.

In my philosophy, you must do speed work all year long so that you never lose speed to any great extent. We start doing speed work at the beginning of the training season. We do short sprints at first to increase anaerobic capacity and natural speed. Everyone comes with a natural speed, especially if you’re coming from a soccer or football background and are used to doing sprints. But if natural speed is not maintained, it is easy to lose. Many athletes who have not been exposed to a speed sport have the misconception that they can just go out 2 or 3 times, do some sprint workouts and this will make them faster. The reality is that the process takes between 14 and 16 weeks before you can measurably increase natural speed. Speed work must be done early and before you add any other volume or longer-intensity workouts. It’s a simple concept, but it’s a little complicated in terms of what you must do to follow the process. The basic principle is that we are trying to get to as high a speed as possible before we put on the volume. This is what we call inverse periodization.

As the training process and athletes start a training cycle specifically for long distance races (½ IM and up), intensity is reduced and volume increased. If the athletes didn’t bring their speed base to a very high level, they’re never going to get faster, because as we know, they’ll lose some speed during the high volume phase. The question I’m sure many of you have is, what about the endurance? If you do focus on speed early in the preparation cycle, will endurance suffer? The answer, and it is important to remember, for an experienced athlete, you don’t need more than 6 weeks to get your endurance back to a higher level. Another thing to remember is that you don’t give up endurance altogether when you do your speed training. Along the way, you are going to swim, bike and run. It’s not that you’re not doing endurance at all, you’re just not doing as much as everyone else. People also forget that endurance is a combination of all three sports. You don’t need to do volume in swimming, biking, and running, but you must do a combination of endurance volume to increase your endurance.

Introducing the Four Cycles of Inverted Periodization

The model presented in Table 1 has four cycles developed for half- and full-iron. These cycles and can be adapted for Olympic distances. The only change would be on the quality and length of intervals we do close to the competition phase, cycle III. That is going to be more specific to the distance. For the half and ironman distance races, I recommend a little longer “brick” workouts and the intensity is mild compared to what I do for the short and Olympic distance races. However, the philosophy is the same and the athletes will be working with the different volumes for the distances. When discussing the ITU athletes I coach, we are going to be working just a little harder on the swim (more quality and volume), and probably one more quality run workout per week, depending on the athlete background, because that is the characteristic of the race. For most of the other athletes that do both races (draft and non-draft), they go through the exact same cycle; however, they wouldn’t do the cycle for volume (IV). The volume they do, especially trough the swim, gives them enough endurance for the distance they’re racing. The quality of some intervals on cycle III is different for different race distances.

The Training Year

To help bring these cycles into a yearly perspective let’s look at some dates.

For the average athlete who tries to peak for races in the summer, June-August, the cycle starts in November or December. It’s all adaptable because, depending on the schedule, I have athletes that must be in peak race condition by May. Depending on their training background, cycle I can be shortened if necessary. However, cycle I is very important because weight training will allow the muscles to get strong enough to support all that speed work that will be done afterwards. Swimming is used to give the minimum aerobic base, at low impact, we need.

Cycle II has a two month leeway, 8 to 16 weeks. The reason for this is that it takes a long time for the athletes to gain speed and the cycle is based on the individual athletes’ ability to gain speed. Speed work is a very painful process. I sometimes have problems with my athletes. They go through the first couple weeks feeling really sore because their bodies are not used to the intensity and this takes some time to overcome. But they start getting used to it.

Now comes the question of how much speed is enough? What are the indicators in this large window of 8-16 weeks in cycle II to know when it’s time to move to the next cycle? This is a question I’m sure many coaches would like answered. I use two indicators—the more efficient one is a lactate testing. That is a way to find out what the athletes can do in anaerobic capacity. We do a 400m, all-out sprint test (after a proper warm up and stretch) to see how fast and how much lactic acid they can accumulate in that period of time. Let’s say an athlete has a really low speed—his or her result is going to be about 8 mmol/l. The goal becomes getting an increase of 30%-40% of that production of lactic acid for that period. Some athletes reach that level sooner, others later. Some of us never reach that level.

Lactic acid is an indicator of how hard the muscles are working, more precise then heart rate that could vary with dehydration, health and etc. It also tells me the limitations of the muscles. After 5-6 weeks of speed work, we test again and the difference is amazing.

For athletes with whom I don’t have direct access, we go exclusively by time. They tell me how fast they can do an all-out 400m on the track.

It’s important to mention sprint technique and efficiency in running. For triathlon, many of us don’t know how to be efficient in doing a short sprint. Time needs to be spent on running techniques.

Inverted Periodization Consideration for Master and Beginning Level Triathletes

The program outlined in Table 1 is for elite and experienced athletes. This is because of the volume and intensity. However, the method is adaptable to any athlete. If you take athletes who haven’t done any endurance work, they may need more endurance to begin with. As we know in triathlon, it is an endurance sport and you need at least the minimum endurance training. If you get an athlete who is a true beginner but who has done at least a year of endurance exercise and has a minimum endurance base, you actually can use the same technique. Of course testing has to be milder because s/he isn’t used to the intensity. Taking an example from cycle II, let’s say I ask the athletes to do 2 sets of 6 100m sprints all-out. For beginner athletes, I will probably ask them to do 2 sets 3 100s and not all-out from the beginning, but accelerate into the sprints. This is done to prevent injury. Endurance, in this case would be a by-product of speed training.

If I get beginning athletes with sprinting backgrounds, I would skip this phase and put them straight into more aerobic power/oxygen economy, which is cycle III. It depends on the background of the athletes, but the majority of athletes I have worked with have no background at all. They started in triathlon because it was fun. Consequently, I start a little slower, especially if they are older. This is to control as much as I can. It’s funny to say but especially with older athletes, they are the ones who need more speed and strength training than anyone else. They are the ones who have lost the most. That is where they are going to get their gain—not on a bike 5-6 times a week, but rather in a gym and doing speed work. The older an athlete is, the more emphasis needed on speed and strength. Take me for instance—I am 50. If I want to race at the same level I raced 20 years ago, I spend more time working core, strength and speed then I did when I first started. When you are younger, you have more speed and strength but you end up losing it.

What happens is athletes come to me and say they have no speed. It’s not that they don’t have it, it’s that they haven’t used it in a while. What athletes like is to get on their bike or go for a run for an easy, long bike/run. The fast switch fibers have been sleeping too long and they just haven’t been using them. They must wake them up.

Selling the Concept to Clients

This different approach, which has a good deal of discomfort built in, may not be appealing to many athletes. I explain to them to think about how they have prepared in the past. Why then do they think they must do all the volume at the beginning of the year if they are only racing in July?

They have all been through the following scenario—first track workout of the year, fast age groupers get to the track to run 400s in 90 seconds. They run and can’t believe how slow they are. That is very frustrating and it makes them want to stay away from sprint and speed work all together. Every time they go back, it just feels so hard because they haven’t done any speed in months.

Let’s say they kept up with the speed but getting close to race time, they think they need more volume because they want to get to the race with enough endurance, so they start mixing both. That is what causes them to crash. They all identify themselves with that situation because we have all been through it. It is very painful when you feel slow because you go right into the more specific speed work. That is one thing we don’t do because we start very short, high-intensity intervals. They go the 400, 800, 1mile or 1km repeats and it’s very slow and produce lots of lactic acid, slowing recovery and giving them severe muscle fatigue. Then they have to go on a 3 or 5-hour bike ride, depending on the event, and they freak out. They feel slow, but they don’t want to give up the speed work nor the volume. They mix both and start feeling fatigued again and the race is now 4 weeks away, so they add more volume, freak out, and end up having a mediocre race.

We show them that by doing things in reverse, building a strength and speed base first, they will avoid the frustrations of trying to get speed back or doing too much and ending up over trained or even worse, injured. Once they look at it, it starts to make sense. Once they try it, the results speak for themselves.

Table 1

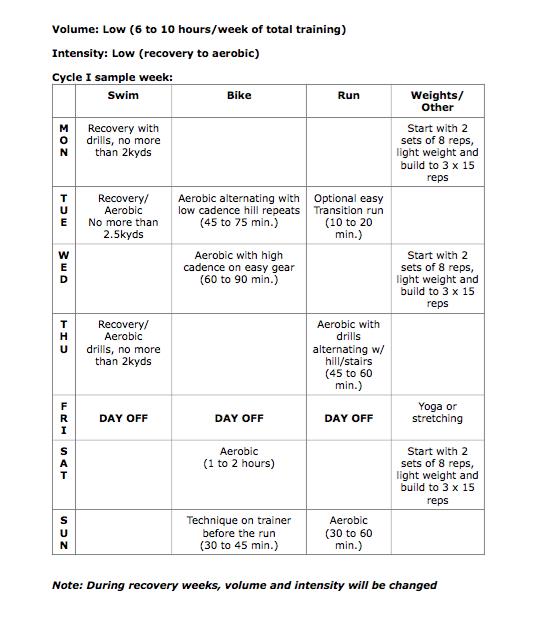

CYCLE I – Strength and Technique (6 to 8 weeks)

The goal of this cycle is to improve technique and develop strength. Because of the reduced volume and time spent training, more emphasis on technique can be done. Weight training and sport-specific strength training for swim (stretch cords and longer sets using paddles), bike and run (hill repeats, stairs, etc.) will give necessary base for the next training cycle, which increases anaerobic capacity and prepares the muscles for high intensity intervals. Technique drill sessions should be applied at least twice a week for each discipline (incorporated into aerobic/recovery workouts) and possibly videotaped to analyze and discuss with the athletes. A minimum of aerobic capacity (base) training is needed and recommended. Too much endurance will not let muscles build or increase in anaerobic capacity. Note: weight training should be the last workout of the day

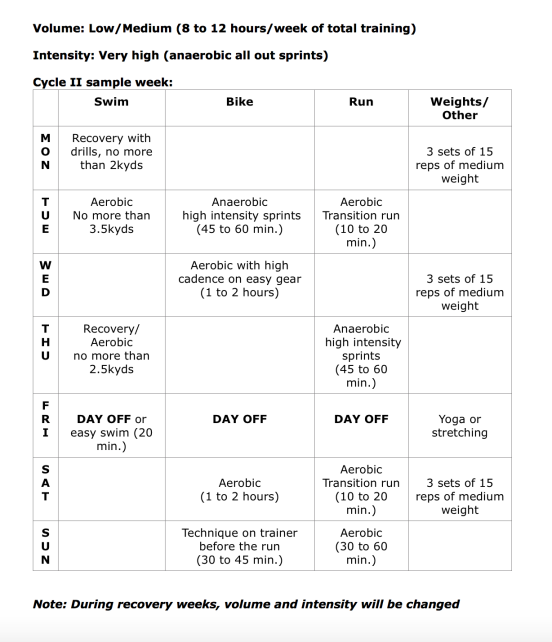

CYCLE II – Speed and Strength (8 to 16 weeks)

Anaerobic capacity/Muscle fibers switch phase

This is probably the most important cycle of training. Speed is always overlooked by most endurance athletes who love high volume training. They all believe that speed is for sprinters; it’s painful and not recommended. Everyone has a natural speed (percentage of Type I and II muscle fibers) or a speed developed by other sports where Type I fibers were exhaustively worked. Working on increasing your anaerobic capacity (speed and strength) will benefit your aerobic pace in the future. A higher anaerobic capacity helps athletes tolerate LT interval sets and increase aerobic pace. This cycle focuses on increasing the athletes’ natural speed through high intensity and very short intervals. To develop anaerobic capacity, more time needs to be spent with repetitive and painful sprints. Endurance is obtained mostly trough swimming and cycling.

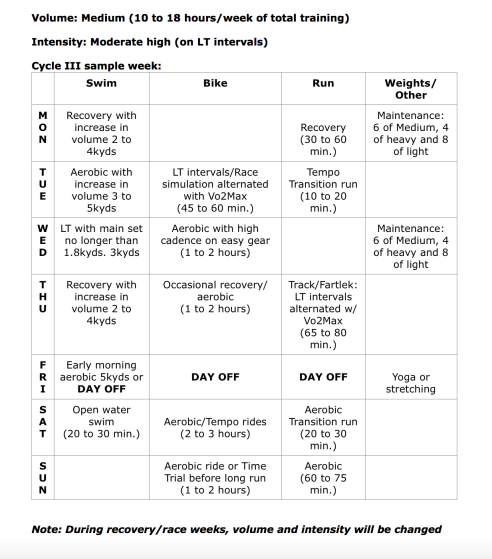

CYCLE III – Aerobic Power/Oxygen economy (6 to 12 weeks)

Race specific and increase in pain threshold workouts

On this cycle the goal is to increase your pace at LT and maximize the percentage of your Vo2Max. Also the focus is to create muscle memory where the body won’t be surprised by the intensity and speed of the races. It’s easier mentally and physically to race when you have experienced the same intensity before. Time spent at LT will be carefully planned to avoid injuries, over training or decrease in aerobic capacity.

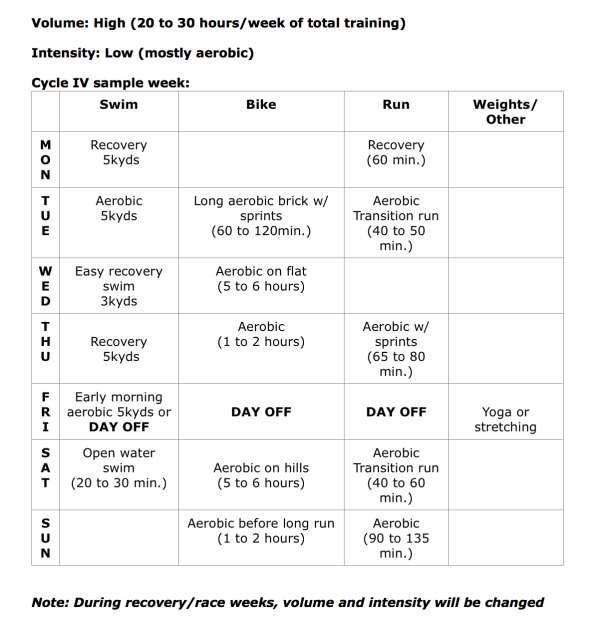

CYCLE IV – Aerobic Capacity (4 to 8 weeks)

Increase endurance for long distance races

Endurance sports rely mostly on aerobic capacity (85% of your race), so for athletes doing long distance triathlons like ½ IM or Full, this phase is crucial and mostly aerobic with some “spices” of anaerobic capacity. It’s important to get to the race with the highest aerobic capacity possible, that’s why the “slow, long workouts” are done at the pre-competition phase.

More Information Please!

To learn more about inverse periodization for triathletes, contact Sergio at sergio@sbxtraining.com